from the archives

Excerpt from OSMOS Issue 17

The Forever Archive: The Untitled/1919_Torso, 2015

ONYEDIKA CHUKE IN ROME

CLASSICAL REFLECTIONS

BY MARY STIEBER

The work of New York artist Onyedika Chuke is beauty-driven, evocative, haunting, and ethereal; neither abstract nor representation- al; and timeless and placeless, not to mention astonishing in its technique. A defining characteristic of Chuke’s work is his deftness at culling imagery from multiple sources and facilitating a dialogue, remarkably free of pre-conception, among varied civilizations, time periods, and geographical places. His creative goals are such that each phase of artistic production is suggestive of, and interlaced with, the next phase. Each resultant assemblage, to adopt an analogy from textual criticism, comes with its own “apparatus criticus” that traces in brief the divergent histories of the manifold ideas he engages. To reach any sort of finality, Chuke’s work requires immersions in multiple cultures, ancient and modern, a process often involving visits to the places where these cultures’ forms can be directly experienced. To date, he has travelled and conducted research in eight countries, collecting material and ideas for his The Forever Museum Archive, an ongoing project that has occupied the artist since its conception during a trip to Libya in 2011.

Despite, or perhaps because of, Chuke’s Nigerian heritage, he does not think in terms of conventional categories like western and non-western, ancient and modern, abstract and representational. Thousands of years of global art history is but a holistic wonder to him and, as such, a source of limitless curiosity and learning opportunities which he probes impartially and irrespective of style, period, date, or medium. Sculptures of the human body, for instance, are “three-dimensional models” and are conflated with bits of architecture and allusions to history and politics—whatever it takes to convey content. Chuke’s works tend to be conceived and presented as a synergetic grouping involving architectural elements (real or molded), found objects, drawings and diagrams, and sometimes performance relics. He often obscures origins or influences through the use of molds (as in the piece featured on the cover of OSMOS 16), an artistic choice that serves to elide or blur authorship, time, place, and historical reference, resulting in a removal or distancing from reality—what the artist likes to call “magic realism.” Acts of conscious displacement and calculated juxtaposition re-signifies context, thereby dissolving the boundaries between form and content.

The Forever Museum Archive: The Untitled/1919_AK 47, 2015

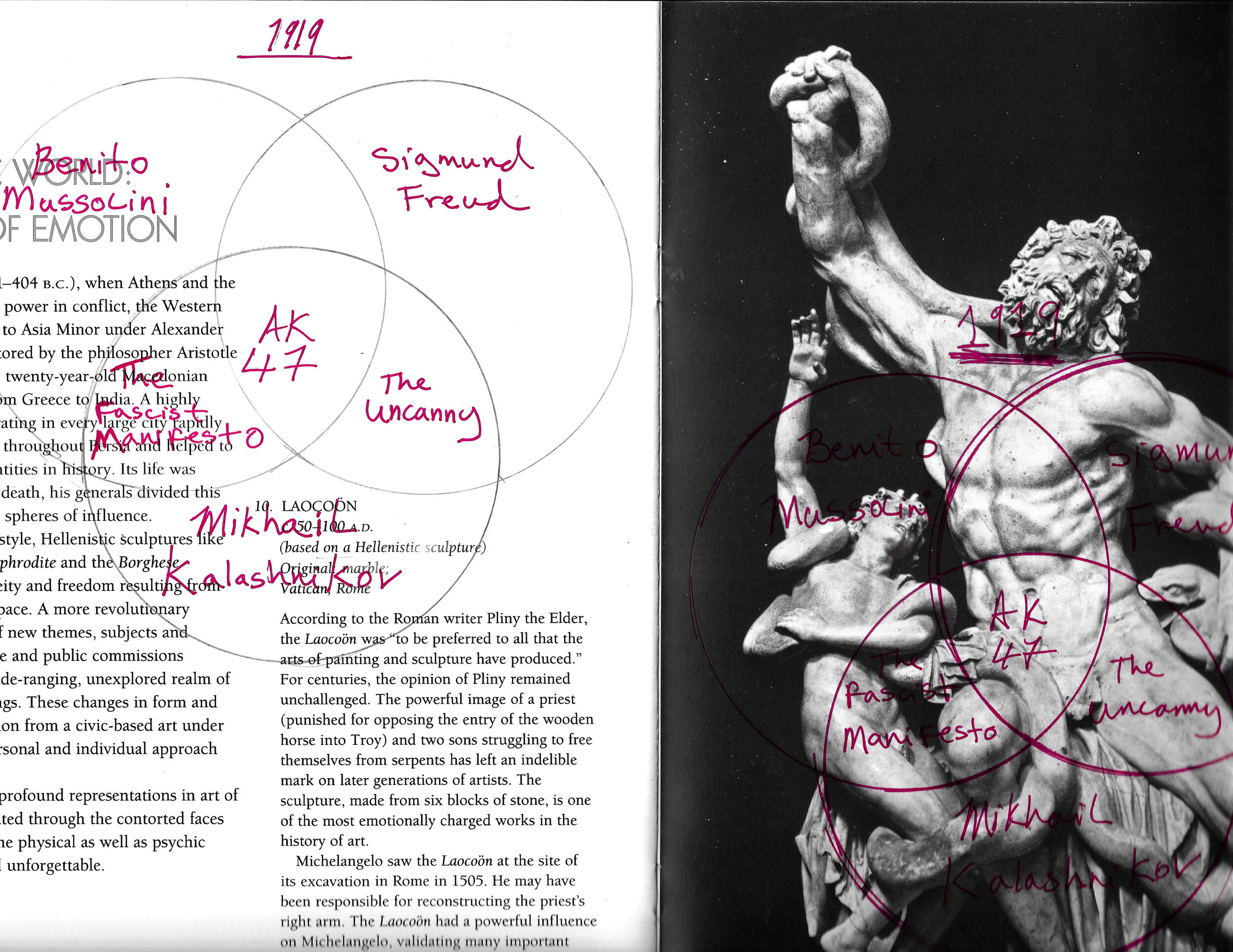

The Forever Museum Archive_The Untitled: 1919

Installation shots from The American Academy in Rome, Italy

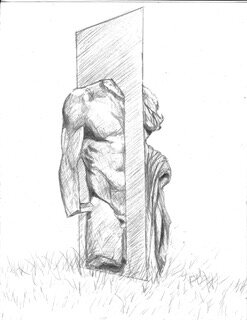

The Forever Museum Archive: The Untitled/1919_Torso, prepatory sketch, 2015

The Untitled: 1919, 2015

Visual Notes from The Forever Museum Archive, 2013-2016

His uses of politics, anthropology, conservation, curation, literature, historical happenstance, economics, and, on the formal side, feudal-era workshop techniques contribute to the elision of time, place, medium, and milieu. The Forever Museum Archive is at the same time refreshingly traditional and new, not to mention timely, as digital technologies have raised questions about the museum’s viability as a venue for housing and curating works of art. The work that Chuke hopes to produce would constitute a colossal contemporary compendium of nature and art, an intercultural and pan-cultural dialogue, together with a utopian vision of his own private world. In his willingness to mine the artistic productions of the past for renewal and re-curation in the present, I consider Chuke a “classical” (but emphatically not a “classicizing”) artist. It is this quality, which has to do with a creative stance in respect to material, form, and method, rather than the rich content of his work, per se, that I shall reflect on in this essay, particularly in reference to Chuke’s cover piece, The Forever Museum Archive: The Untitled 1919/Torso (2015).

First, some context: In May 2015 the artist/archivist was invited to The American Academy in Rome by Peter Benson Miller, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Robert Storr to present an excerpt from The Forever Museum Archive. Chuke’s sponsors stipulated that he live on the grounds and create work over a twenty-day period. Drawing inspiration from his ongoing research for the Archive, arriving with just a suitcase of oil-based clay and sourcing his other materials in and around the environs of the Academy, the artist produced four steel-and-cast-concrete sculptures during his brief residency. The result is a series of works that center on the year 1919 and three concurrent but unrelated events—the birth of the inventor of the AK-47 assault rifle, Mikhail Kalashnikov; the publication of Sigmund Freud’s The Uncanny; and the appearance of Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Manifesto—and examine the coincidence of these momentous occurrences and their impact on global political consciousness. With the clay he brought from home he modeled an eight-foot-long, three-hundred-pound AK-47; with a mattress and pillow that he fortuitously found he cast a military-style bed; and, with special permission, he made a mold of a fragmentary antique Roman torso in the Academy’s private collection. These works were exhibited on the premises of the Academy in 2015 and are now entered into the Archive as The Untitled 1919.

Torso reflects on the architecture and monuments of the Fascist era that were commissioned by Mussolini and remain a conspicuous feature of modern Rome. On the picturesque, rolling greens of the Academy grounds, the gauged and sliced cast hangs close to the ground from a thick steel sheet like a slab of meat, distantly recalling famous paintings by Rembrandt, Chardin, and Soutine. On the other side sits a benign-looking potted palm taken straight, it seems, from a Victorian parlor. The assemblage is meant to evoke, among its references, the fondness of Fascist governments for walls, whether physical or merely psychic. Based upon Chuke’s 2011 research in Libya (an Italian colony from 1911 to 1947), the sculpture is intended to notate the multiple historical layers that underlie this storied ancient land, specifically, the late Roman Empire, the regime of Mussolini, and, most recently, the dictatorial state of Muammar Gaddafi, whose violent ousting began on February 15, 2011, just a few weeks after Chuke traveled in Libya. The palm is a gesture toward the garden setting, a reminder of nature in a more benign mode, as well as a recollection of the actual landscape features of the sites and museums that Chuke visited in Libya. The other two pieces that comprise The Untitled 1919 are a molded version of a military-sized mattress and pillow that the artist found on the Janiculum, alluding to the dream spaces of Freud, and two colossal casts of modeled AK-47 rifles, one exhibited inside the Academy and the other on the grounds, that address from various perspectives the anxieties of warfare (and domestic violence) that this weapon’s unmistakable form evokes.

To this viewer, a classicist by profession, one author comes to mind when encountering Chuke’s work, all the more markedly in Torso, since it incorporates a simulacrum or eidolon of an actual classical artifact. Whether by chance or design, there is much about Chuke’s work that finds its counterpart in Plato’s Republic and elsewhere in the philosopher’s corpus. These important themes, however, I shall have to leave unaddressed, in order to focus more generally on the Platonic overtones of the creative process, especially as I see them evidenced in Torso.

I have called Chuke a classical artist, and this accolade implies a particular kind of relationship with nature or reality. Let us explore some of the implications of the complicated dance between the classical artist and the “real” world to understand what Chuke’s “magic realism” might mean. The Greeks had a word for what an artist does that is enjoying a renewed currency: mimesis. There is no perfect translation; imitation is probably the best. In the Aristotelean sense, mimesis is the act of imitating nature; mimetic realism is the result. Mimesis is etymologically derived from mime, the earliest form of ancient drama. In part because of its origins in the art of acting, there is always an inherent deceit, or counterfeit, associated with the product of the successful mimetic act. A mimetic object may be a near-perfect facsimile but, whatever it is, it is never the real thing. Chuke’s habitual use of casts or molds in the creation of his works thrusts them into this ontological space, playing a perceptual and conceptual game with reality that has provocative, and often unsettling, consequences.

It is important to bear in mind that there is always an inherent artificiality in a subject so viewed and portrayed, a realism which is only apparent—such is the case with Chuke’s pieces that feature figural imagery in one form or another. Plato, in Book 10 of the Republic (596d–598d), famously, or infamously, critiqued visual artists for this very lapse, that is, producing work that is not only not real but rather “two removes” from reality—reality for Plato existing somewhere above the sensible, sublunary world in a world of forms, or universals. Chuke’s Torso presents a direct challenge to this hugely influential view of art, which has been debated for centuries. This is work that is deliberately at two or, on Platonic terms, even three removes from reality, exploiting and even celebrating the distance as semiotically significant, indiscriminately reverential toward both the imitated (an athletic male torso) and the imitation (a consummate testimony to the ancient Roman marble-carver’s art). With AK-47’s more disturbing content, two removes from reality is reassuringly welcome, particularly in light of the colossal scale of the cast of the modeled rifle, though the awe or reverence (for the future destruction to be unleashed by Kalashnikov’s invention) is reserved for something far less exalted. Deliberately staking out territory in this two-steps-removed Platonic realm, I would argue, is in the end a form of idealization, of deferential distance from a reality that is potentially un- nerving. More importantly, it constitutes the conceptual habitat of Chuke’s works, whatever their distinctive content, and as such, a primary locus for meaning.

Visual Notes from the Forever Museum Archive, 2013-2016

The transformation of some facet of nature/reality into art via human ingenuity applied to real-world materials, whatever its motivation or at however many removes, can never be complete. This natural state of incompleteness is the formal terrain that Chuke’s work occupies, or rather, hovers over: To be complete is never the goal, and the molds only serve to increase the sensation of partial removal. That incompleteness is built into the form from its inception might be explained as conscious emulation of the fragmentary nature of many of the antique works of art that Chuke has encountered in his travels, but that would be too easy. As it is, many classical artists of the past have proceeded only so far toward completion of a work and then stopped, possibly owing to some subliminal fear of hubris. The mythological figure of Prometheus, the maker of humankind who was punished by the gods for introducing fire to mortals, provides the archetype of what could happen to an artisan who inadvertently invokes the envy of the gods. These artists are careful to reserve a trace of facture (that is, visible evidence of having been made) as testimony that this particular created form is not real but a work of art two removes from reality, as if defiantly throwing down a gauntlet to Plato. The deliberate alterations made to the original Roman torso in Chuke’s concrete cast of it stand as especially bold signs of facture. Even Michelangelo often left statues unfinished. In the case of the David, the top of the head was left rough to prove that the sculptor had used the whole block for the carving. A couple of things might explain why this was important: Leaving a bit of the surface of the block in its quarry state would stand as evidence that the material it- self—in this case, a colossal marble block, abandoned in frustration by a previous sculptor—had been successfully conquered by this one, but also, perhaps, it was a way to certify in perpetuity that the image was made by mortal hands. Chuke likewise harbors a colossus in his studio, in the form of the trunk of a large tree that he rescued from a New York City park, which he has yet to assail and conquer, perhaps for similar reasons. The same thinking might be applied to the twin colossi of the AK-47s. Unfinished works of art bring the artist and the viewer face-to-face with the differences between art and life, with the nature of the creative process itself, and with ways of thinking about any handmade object with a reference point in the visible or sensible world. They create confusion about boundaries and confound accepted notions about what is art and what is real. The fact that Chuke’s Torso is cast in concrete (an ancient Roman innovation, by the way) rather than the usual plaster is suggestive of a nod toward the permanence that eludes the crafted object that is two removes from reality, in Platonic terms, the world of forms or ideas.

As a final reflection, what accounts for the artistic dedication to the pursuit of beauty so keenly felt in the presence of Chuke’s work? And when the subject is a concrete-and-steel cast of an AK-47, is that a disconcerting beauty? Beauty, it almost goes without saying, is a core principle of classical art and thought, and a constant leitmotif, if not guiding principle, for Plato throughout his twenty-seven dialogues. This pursuit may be the single most important qualification for any artist to be considered “classical” and why I see Chuke in that tradition. Beauty, too, is inherently artificial. It too can be said to be a form of idealization. One could say that nature is perfected, done one better, but that would be an unfair, although not an entirely inaccurate, presumption. However, if I am correct to characterize Chuke’s molded figures as idealized, the forms of nature/reality are reduced and what is left is disguised with great deliberation but not eliminated: The Roman torso, gouged and penetrated as a sign of the artist’s intervention in Torso, retains its perfect classical beauty, rendering the piece all the more disruptive of the viewer’s expectations of how a work of classical Greek or Roman art should look. The AK-47, on the other hand, is magnified in scale to increase its ferocity, but as a highly developed machine perfectly suited to its intended function, the beauty of its form is intact. Whatever idealized images such as these are expected to convey are subject to the fact of their being preternaturally beautiful, if to vastly differing effect. The upshot is that nature is bested again, even Plato would have to admit, by the universal idea of beauty, whose form is accessible, apparently, only to the artist who knows where and how to look for and identify it (Republic 5. 472d and 6. 484c-d). However, this pursuit of beauty on the part of artists and other craftsmen, in Plato’s formulation, is not just for its own sake; it serves the polis (city) and hence has a political role to play, quite literally. Perhaps it is fitting to let Plato have the last word, in an excerpt from what may be his strongest statement on the primacy of beauty, bringing it down from the world of forms, aptly for Chuke’s work, in its most imperative, of-this-world dimension, the political: “But rather, [for our ideal city], we must seek out the artists who are naturally able to track down the true nature [i.e., the form] of beauty and fine design, so that our youth can benefit in all ways from living in a healthy environment....” (Republic 3. 401c)

The Forever Museum Archive: Dome and Double Nymph, An Architectural Template for Spiritual Worship, 2012