from the archives

Excerpt from OSMOS Issue 19

STEVEN REINKE

The Hundred Videos

By: Kenta Murakami

1. Excuse of the Real, 1989, 04:31

6. Emergence of Democratic Memory, 1991, 02:58

10. Barely Human, 1992, 03:25

2. Family Tree, 1989, 03:30

7. Speculative Anthropology, 1991, 02:30

11. ROOM, 1992, 04:01

3. Watermelon Box, 1991, 00:46

8. Why I Stopped Going to Foreign Films, 1991, 05:19

12. Michael & Lacan, 1992, 10:56

5. Eleven Dreams, 1991, 06:32

9. I Am Not like You, 1991, 02:10

16. After Baudelaire, 1992, 02:22

The first and last time I watched Steve Reinke’s The 100 Videos, a series created between 1989 and 1996, I was in college. A professor of mine, who was a student of his, had recommended I watch them and at the time they were all linked on the artist’s website. Huddled over a laptop in the basement of my school’s library, I began clicking through the links, one after another, and felt Reinke’s voice infect me with weird ideas. That voice, which narrates the majority of the relatively short clips, has a staunch innocence that makes you want to believe what he says, despite the stories’ frequent implausibility or the narrators’ contradictions.

In the first video, Reinke describes with quiet enthusiasm his desire to create a documentary, “like everyone else,” about AIDS. He explains how “documentary material is usually more interesting than anything [he] could imagine,” and, with presumably feigned ignorance, how the format favorably has what he calls “the excuse of the real”: a notion that because this material purports to reality, he can’t be held responsible. While this piece just precedes the explicit identity-politics battles waged throughout the 1990s, the series was universally described during that decade as ironic. I don’t doubt that Reinke is aware of himself—his prose is investigative, with atheistically told psychoanalytic babble often bubbling to the surface–but I insist that his naïve performances aren’t entirely facetious, either, despite how quickly his documentary moves into fiction or how comedic his method of delivery can be.

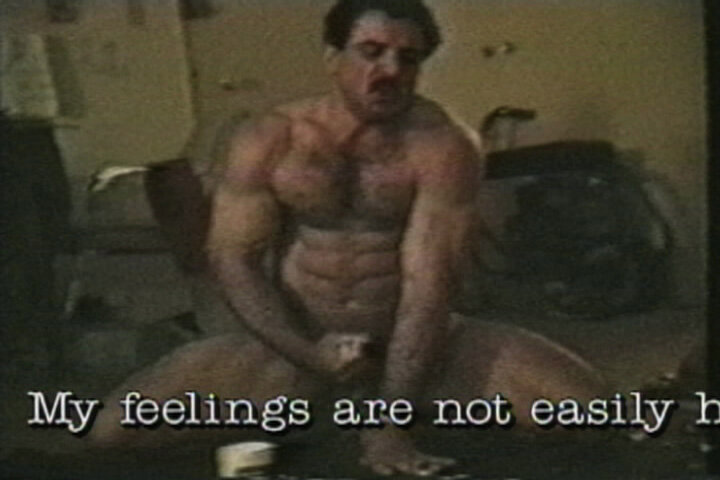

Recognizing–with the possible exception of trauma–that reality is only ever mediated, Reinke understands the arbitrariness of images. In describing his proposed film, he explains that he would like to show home movies from a dying white anglophone homosexual male subject’s childhood, but that if he didn’t have any, that another’s could be used: “Everyone's home movies are basically the same“. Language is a virus, after all, and it will quickly infect whatever that thing is we call reality. In his hundred videos, Reinke’s voice, largely severed from his body, floats among images, contaminating them with its weirdness and being contaminated by them in turn. Moving ambiguously between found and staged low-fi footage, the videos are a concatenating series of disjointed memories, fantasies, and facts. That you cannot always tell whether the footage or audio was created for the videos by Reinke himself or for some folkier, more genuinely perverted manner—if that’s possible—is what makes them fun.

Like a certain brand of believably amateur porn, the appeal is a kind of realism found not in physical rupture or shock, but in a banality, awkwardness, or candidness that cannot easily be performed. In the ninety-second video, Notes on the Uncanny, he speaks to the feeling that much of the footage he employs, because of its datedness and vernacular form, “ha[s] a quality of disturbing familiarity, a famil- iarity which withdraws and causes [him] to become disoriented.” If you are a white anglophone homosexual male (or at least tangentially close to these identities), this false identification with the images, as well as the intimacy of Reinke’s disclosures, creates an environment in which the nostalgic, disoriented videos and thoughts enter and exit you freely as they are found to be either recognizable or abject. They are abject less for anything actually disgusting or gross as they are from a certain cultivation of uneasy boundaries, an experience in which you may be made uncomfortable but want to see more.

In the sixth video, titled The Emergence of Democratic Memory, Reinke describes the sort of pseudo-scientific mapping of memories across the brain by the Canadian neurosurgeon Dr. Wilder Penfield. Like the doctor, who would prod his patients’ exposed brains with a micro-electrode to trigger random memories, flashes of light, or smells, the videos feel like a grab bag of neurological misfires. While memories, which one video refers to as sub-routines of desire, are easily miscon- strued, Reinke moves through them like an anthropologist, logging them unquestioningly. This notion of cataloguing desires is a recurring concern. In the following video, Speculative Anthropology, he muses: “I want to return to that time when the world was an unfinished ethnographic map and it was possible to imagine a tribe with a specific set of characteristics and be fairly confident that they would eventually be discovered, naked and scarred and superstitious. But now that hope has degenerated into faith. Now that we have found whatever is out there and can successfully determine what they will develop into, the imagination is useless.”

In many ways a refusal to comply with this failure of imagination, The 100 Videos imagines desires that, though perhaps already present or named (he doesn’t believe in the notion of a subconscious), are overly pathologized. Reinke fantasizes about being a single-cell organism, a logo, a sex alien, a four-month-old child, Jeffrey Dahmer in the grave, various “tribes.” He displays with blunt sincerity an infantile eroticism that precedes an understanding of function, or perhaps more realistically a queer eroticism of disregard. It regresses impossibly through words, past words that seem to seep and spill off the brain as he heads back to some kind of prelapsarian semiotic chora; an exploratory, adolescent, osmotic exchange of fluids, the fluids of images and texts that feed off each other and grow into something they’re not, or perhaps not something they’re not, but— rather like bacteria on agar—into something there but not seen.

17. Language of Rats, 1992, 03:30

32. I Love You, Too, 1993, 00:52

41. Pioneer, 1994, 01:13

19. Introduction to the Logo, 1992, 01:21

35. Instructions for Recovering Forgotten Childhood Memories, 1993, 02:41

43. Vision (With Birds), 1994, 05:01

20. Deaf, 1992, 02:54

39. Editorial, 1994, 01:34

58. Minnesota Inventory, 1995, 10:37

25. Pus Girl, 1992, 01:25

40. Understanding Heterosexuality, 1994, 01:28

62. Black Heart, 1995, 02:08

29. Little Faggot, 1993, 02:34

49. Monologue (with Provocation), 1994, 02:51

63. Box, 1995, 02:35

31. Lonely Boy, 1993, 08:20

56. Jin's Dream, 1995, 01:25

64. The End of My Death, 1995, 02:15